- Home

- Ross, Hamish

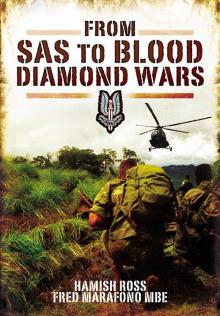

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars Read online

We are the Pilgrims, master; we shall go

Always a little further; it may be

Beyond that last blue mountain barred with snow,

Across that angry or that glimmering sea.

Inscription on SAS memorial clock tower taken from James Elroy Flecker, ‘The Golden Journey to Samarkand’.

Conflict diamonds (sometimes called blood diamonds) are diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments, or in contravention of the Security Council.

UN Definition

First Published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright © Hamish Ross 2011

ISBN: 978 1 84884 511 4

ePub ISBN: 9781848849761

PRC ISBN: 9781848849778

The right of Hamish Ross to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the

Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 10pt Palatino by Mac Style, Beverly, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK

By CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and

Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Foreword by Peter Penfold, CMG, OBE, Former British High Commissioner to Sierra Leone

Acknowledgements

Part I

1. The Master’s Company

2. The Chief

Part II

3. Executive Outcomes

4. Democratic Vista

5. Fubar

Part III

6. Bokkie

7. Carrying the Can

8. Air Wing

9. Operation Barras

Part IV

10. Last Enemy

11. Paying Back the Shilling

Appendix I: Hostage of the RUF, Swiss Honorary Consul-General, Rudiger Bruns

Appendix II: Comparative Costs: Executive Outcomes, Sandline, Juba Incorporated and UNAMSIL

Appendix III: Testimony at the SCSL on behalf of Chief Hinga Norman, General Sir David Richards, Chief of General Staff, UK

Appendix IV: Observations on the Autopsy of Chief Hinga Norman, Dr Albert Joe Demby, Former Vice President of Sierra Leone

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Foreword

Our country is rightly proud of its military forces, not least our elite SAS. But what happens when these well trained and highly motivated men and women retire from the regiment? What do we expect them to do back in civvy street? Hamish Ross’s book charts the path taken by one of these remarkable pilgrims.

A couple of years after I left Sierra Leone as British High Commissioner and had retired from Her Majesty’s Diplomatic Service, my daughter went out to Freetown for a while to help at the Blind School there. By now peace and democracy had been restored. But this being Africa you could never be certain what lay around the corner, so before she left I gave Catherine a telephone number and one name − Fred. I told her that if there was any trouble at all just ring Fred and I was sure that he would help her. Such is the confidence, trust and admiration I have for this remarkable man − one of those unsung heroes who emerge in conflict situations like Sierra Leone. Fred Marafono is one of those people who ‘cross the river’ for you, to quote the SAS saying. I am very pleased therefore to write the foreword to this book.

How times change! Twelve years ago I was reprimanded by my government and pilloried in the press for having contact with so-called ‘mercenaries’. Nowadays private security firms are a vital part of the British Government’s efforts in places like Iraq and Afghanistan. But even back then some of us, not least the Sierra Leone people themselves, already knew what a vital and positive role the private security firm Executive Outcomes had played in fighting an insurgency and protecting the population. This book reveals how a force of just 200 trained and disciplined men achieved what a subsequent force of thousands failed to initially. What EO achieved in Sierra Leone was down to the likes of men like Fred Marafono; however, even amongst his colleagues, Fred was special.

But this book is as much about Chief Sam Hinga Norman, a man that both Fred and I crossed the river for. He was another African in the Nelson Mandela mould who fought for the cause of justice, peace and democracy. Sam Norman’s arrest, detention and untimely death remains a huge blot on the Sierra Leone story. Hamish Ross’s book reveals much of the real truth of the man, very little of which emerged in his shameful trial as a war criminal by the Sierra Leone Special Court. In the eyes of most Sierra Leoneans he is a national hero.

However, perhaps the real heroes of this book are the ‘ordinary’ Sierra Leoneans who sacrificed so much for the cause of peace and democracy − the countless thousands who lost their homes, their limbs, their loved ones and their lives. It was their courage and sacrifice which prompted people like Fred Marafono to cross the river.

Peter Penfold

Acknowledgements

Many of those whose input I wish to acknowledge gave their time and effort because of their regard for Fred. First of all, therefore, I want to thank Fred for calling on his wide network of old comrades and friends and for ensuring that our collaboration worked so smoothly.

His former comrades: Alan Hoe, Pete Flynn, Simon Mann, Roelf van Heerden, Tshisukka Tukayula De Abreu, Cobus Claassens, Tijjani Easterbrook and Alastair Riddell all gave support. I particularly want to thank Juba Joubert for his sustained input.

The Secretary of the SAS Regimental Association was most supportive and is greatly in my debt. I am also indebted to Doug Brooks, Rick, Jim Hooper, Tim Spicer, Michael Grunberg, the Rev Alfred SamForay, Gregor Ross and Ewan Ross. Special thanks are due to Peter Andersen, whose excellent online archive has been a valuable resource.

I would like to thank Rudi Bruns for writing an account of his experience as a hostage of the RUF and also Dr Joe Demby, who gave permission to quote his report on the autopsy of Chief Sam Hinga Norman. I wish to thank the Norman family for giving me access to the diaries and notebooks their father wrote in prison, and especially to Florence Norman and Sam Norman Jr for their support.

Finally, I am most grateful to Peter Penfold for his contribution to this work and for writing its Foreword.

Part I

Chapter One

The Master’s Company

Stirling was a master of t

hat art and it got him good results.

Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne, Journal, Montevideo, 20 December 1945

It all began with a phone call. One Friday evening in May 1985, Ian Crooke, Second in Command of 22 SAS, rang Fred and told him they were going to meet someone in London the next morning; he would pick him up between 7 and 7.30 am, and, as an afterthought, told him to bring a tie. Travelling in civvies on a job was not unknown for Squadron Sergeant Major Fred Marafono MBE; during his twenty-one years in the SAS it had happened before. Fred was not his given name though, it was Kauata, and he was born on the Fijian island of Rotuman. Instead of pursuing his intention of studying veterinary science, first at Navuso Agricultural School and then continuing it in Australia, he was attracted by a recruiting drive on the island, and made the decision, as had his father before him during the Second World War, to serve in the British army.

Not until they were about to join the M4 at Swindon on Saturday morning did Fred asked Ian whom they were going to meet.

And he said, ‘We’re going to meet the Colonel.’ I said, ‘the Colonel?’ And he said, ‘Yes, the Colonel.’ I said, ‘Boss, I feel very honoured, I don’t know what to say.’ And he said, ‘Fred, be yourself. You’ll like the old man. He’s very easy to talk to.’

Ian was right. When they arrived at 22 South Audley Street, David Stirling, founder of the Special Air Service, put Fred at ease from the start: he looked him in the eye, spoke to him as an equal and was in no way condescending.

We sat down around his lovely old wooden desk, it was a lovely desk with a big black panther statue – the statue was beautiful, all the muscles were rippling. And David Stirling offered us cigars and a glass of wine. And then he started to explain to me why I was there. He said that Ian Crooke would explain to me the whole reason why I would be involved. ‘Ian and a few of you are due to leave the army shortly and Ian and I talked about forming a security company to provide employment for some of the men who are leaving the Regiment. Recruiting will be selective and Ian told me that you can do the job.’ I was very honoured and lost for words and only managed to say, ‘Thank you.’ Cigars were lit and we drank a toast to its success before Ian continued to explain the company’s philosophy and objectives and the part that each of us would play in it. My role was to find the recruits for the new company – KAS. And that was the beginning of me landing in the world of security after being in the Regiment.

From that beginning, Fred was to go on to develop a second military career and achieve an outstanding combat record in Sierra Leone’s blood diamond wars. Recruited by Simon Mann for Executive Outcomes, the classic private military company that stopped a war, he would progress from ground force commander to gunner in a helicopter gunship, culminating in supporting the SAS in Operation Barras.

Fred’s journey, however, from SAS through KAS and on to West Africa is not a gung-ho tale of intervention in a war-torn former British colony: his pathway was to become intertwined with that of Chief Sam Hinga Norman, a champion for democracy; it would run up against the cost of commitment to good men when political expediency dominates; and his record along the way raises issues about professional private military companies in conflicts where the western democracies are loath to risk their soldiers’ lives.

But first there was a learning curve to be navigated in the ways of private security companies. Fortunately, David asked Alan Hoe to be a consultant to KAS. Alan had served in the Regiment, and after he left and gained experience with International Risk Management (IRM), he set up his own company, which specialized in kidnap and ransom situations, particularly in South America and Italy. In the light of that background, he was able to offer advice; and eventually, after he got to know him better, he went on write the biography of David Stirling.

He asked me to look at his company and, being brutally honest, I thought that the future looked gloomy. Whilst he had some superb guys there: he had Ian Crooke, Sekonaia Takavesi (Tak), Fred Marafono, Peter Flynn and Andris Valters – all of whom had enjoyed good careers in the SAS; they were still soldiers, very enthusiastic soldiers and they all worshipped David Stirling. But there was no business experience and David himself was never a particularly shrewd businessman. They were trying to be all things to all men instead of looking at the market, deciding on their product and then selling it.1

Opportunities were seized if they came their way. Images of a ship on fire, explosives in the hold, abandoned by its crew and adrift in the English Channel, appeared on television. Alan Hoe prompted them on the sequence they had to go through: Lloyds’ Register to find out the ship’s owners; contact the owners; Pete Flynn, who was also a pilot as well as ex-unit, to charter a helicopter; obtain advice and quotations on best type of fire-fighting equipment. The plan was they would abseil on to the ship, extinguish the fire, and Fred, who had been in the Boat Troop, would sail the vessel to port. They were slow, however, compared to the salvage crew that succeeded in beating them to it and towing the ship away. Alan Hoe’s view was that it could have been done, if they had been quicker off the mark.

They chased and won several small contracts like a Bulgari jewellery exhibition. But it earned the company very little, and they probably overspent on their endeavour to win it. The team lived from Monday to Friday in the top floor of 22 South Audley Street, or the penthouse, as they called it, and they earned a salary of £15,000 a year.

In theory at least, David Stirling’s fame would have brought kudos to a company that contracted with him and ought to have attracted clients. But it did not seem to work out that way.

David had some hugely potent contacts but he rather scared them off, I think, because they could not really get a handle on what he was trying to do. He would talk about starting a mercenary company one day, and the next he would be offering bodyguards and then looking after high value species the day after. He had good contacts like Margaret Thatcher, William Whitelaw and Dennis Healey as well as many influential business friends but he got little out of them because, I think, he frightened them off.2

One contact he did not frighten off was Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, who was the first president of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). It was well-known that elephant and rhino were endangered as a result of poaching for tusk and horn. The poachers and hunters did not make much from a kill, but the ivory and horn was finding its way along a route that led through the Middle East to the Far East. It was suspected that at least one Asian embassy was behind the trade: rhino horn was in high demand in Asia as a traditional medicine. Stirling spent years in central and eastern Africa, and had influence in some quarters. Alan Hoe was involved in setting up an infiltration operation.

I went over with Ian Crooke on one occasion to meet Prince Bernhard to discuss the proposition. We spent the best part of a day with the Prince talking about the project, and into the equation he brought John Hanks, who was a senior executive within the WWF, and was very much in favour of the project.3

Funding for what became known as Project Lock came from the WWF and, it was believed, from a department of the South African government. The operation was aimed at all parts of southern and central Africa ‘where the survival of rhino was threatened by poaching,’4 A small team, including Ian and Fred based itself in South Africa; there was an office in Johannesburg and another in Pretoria.

And it was very, very enjoyable. We were attacking at two levels: one group was to do the training with the game wardens in a park in Namibia. That was our first operation, to know the animals, to know their habits and everything. And then the other group were stationed in a base and had to try and get to the people who were actually dealing in these endangered animals. The decision was made that since I look like a Malay, and I could speak Malay − there’s a very big Malay community in South Africa, in Cape Town −, my background was that I was to be a Malay from Woodstock, overlooking the harbour in Cape Town. That was the cover.

But you cannot operate in South Africa without the approval of the South African gove

rnment. Whether you like it or not that is the reality. We had two very nice business people who were very helpful. One of them ran a security company, and the other played a supporting role. The one who ran the company used to work for the South African intelligence service. He was very helpful; he was the one that made it possible for me to get into the network. He had the connections for me to get into the security company network. I eventually went across to Zimbabwe.

The thing was that before you could be accepted by these people, you had to be ready to show that you were interested in the endangered species, the rhinos and the elephants. And an English couple that ran the reserve for King Maswadi III were very helpful in showing us the different types of species: the white rhino, the black rhino. We learned a lot about the animals, we’d see them and learned what to do and what not to do. We then had to find out the people who were wanting to buy these animals, and go and try and make a deal. And I would be the seller.

For my first deal in selling a set of black rhino horn to a Chinese man in Manzine, we recced a site suitable for a team to set up a covert hide to photograph the whole operation. The car boot was rigged up with a covert microphone and the position where I was to stand forced the client to face the cameras. And it was a Chinese man who owned a restaurant. At the end of the deal I was supposed to collect the money. But of course, that was the thing, nobody goes around carrying a big wad of money. So he said, ‘Come to the restaurant to collect the money.’ What do you do; do you say no? I said that I’d come that evening. And I went back and I told the others. I was given a right telling off: that is risky, you’ll never get the money back. But a promise is made, I had to go and get the money; you have to carry it through; you just don’t turn around – whatever it is, it is.

I went, but the plan was that Nick Bruce (one of the team) would cover me in. He was to check out the place, looking for any suspicious signs, order a meal and when I came in half an hour later, if everything was OK, we were to make eye contact. I was to go to the bar, order a drink and ask for the boss. If things looked suspicious, Nick would cough when I was at the bar before he paid for his bill and left the restaurant. Nick was to go back to base and wait for my return.

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars