- Home

- Ross, Hamish

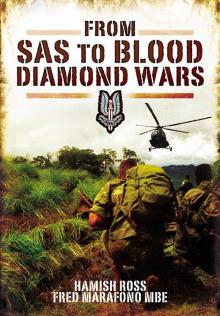

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars Page 2

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars Read online

Page 2

So the boss man came. We shook hands, and he said, ‘Come to the kitchen and meet my family.’ So I met the family. Then he said that this was the amount we agreed but there was slight damage to the commodity – to the rhino horn – so instead of X amount he would deduct 7%.

That was the beginning. And then we were to go to Swaziland, Botswana and Zimbabwe.

Although KAS was beginning to get into the illegal marketing at this level, what it was not providing was conclusive evidence of the source promoting the poaching. Before they could refine and develop their approach to penetrate a deeper level of involvement, the whistle was blown on them. Not by embassy officials who may have felt they were being accused, but from inside the WWF. It was discovered that the WWF was funding mercenaries.

There was a lot of criticism bandied about when the media got hold of the story. John Hanks lost his job, a chap who had been an ardent member of WWF for many, many years. Prince Bernhard took a lot of criticism over it, but I don’t remember the press ever giving a fair, unbiased view. But these things happen in life. If you’ve got the name David Stirling linked – you’ve got controversy and the media rake over old ashes.5

President Mandela of South Africa later set up a commission headed by Judge Mark Kumleben to investigate the smuggling of ivory and rhino horn. The commission confirmed that ‘the covert unit operated against smugglers in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Namibia and other southern African countries.’6

However, David Stirling would not have achieved what he did in 1941, founding a unit in the North African desert that was destined to have a such a distinguished history throughout its first seventy years, if he had been deterred by the Jeremiahs of this world.

He had expectations of the men he recruited for KAS from their counter-terrorist experience in the Regiment, and through his contact with a leading figure in a key industry, he floated the idea of presentations to company executives on strategies to prevent terror attacks. Some of the team carried out surveys, and did a risk analysis. The result was that senior, hard-nosed executives, in spite of their disbelief, were forced to listen to presentations from, what they privately considered to be, a couple of madcaps depicting terrorist threat. Indeed, in the 1980s, such scenarios (which will be passed over here) might have sounded like some fantasy for a film script. They would not be reckoned improbable today.

A great plus factor in a small security company comprising former members of the SAS, combined with Stirling’s style of management, was that they were able to express and develop forward-looking ideas that Stirling, through his contacts, could bring to the decision-maker level. Ian Crooke, for example, explored with like-minded retired members of US Special Forces the idea of a joint UK/US operation,

whereby either government, or indeed any other approved government, could − if they had on their hands limited intensity conflict − avail themselves of a mercenary force that was composed of ex-US and ex-UK Special Forces soldiers.7

However, this was not to be a covert force designed to carry out the kind of work often attributed to the CIA in the past of destabilizing a government that was hostile to US interests in a particular region. This idea, which was prescient, was for limited conflict situations – of the kind, as we shall see later, in Sierra Leone – where there was a threat to an established government on the one hand, and on the other, a sympathy and a willingness by the west to give support, but a reluctance for political reasons to risk US or British soldiers’ lives. The idea got as far as White House level: David Stirling and Pete Flynn went to the States. Stirling met President Ronald Reagan; Pete was not present at the meeting, but he met Vice President Bush.8

Nothing came of the idea at the time. Yet only a few years later, a private military force was founded in South Africa of the same sort of calibre as the KAS concept; Fred was a member of it, and it stopped a rebel war at the request of the recognized government of Sierra Leone.

After Stirling died, new ownership took over the company. Fred and most of the team left. Fred’s hallmark is his loyalty, a loyalty that came to him naturally, from his heritage; such was his attachment to David Stirling that when the SAS Regimental Association held its memorial ceremony in honour of its founder, at Ochtertyre in Perthshire, Stirling’s home area, Fred flew especially from Sierra Leone to attend.

It was to be in this country that he would perform some of his best work, fighting insurgency in conflict diamond regions.

Chapter Two

The Chief

Pike Bishop: When you side with a man you stay with him.

from the film The Wild Bunch, directed by Sam Peckinpah

The team of six, led by Project Manager Alastair Riddell, formerly a senior officer in the Parachute Regiment, touched down at Lungi International Airport, Sierra Leone at around 9.30pm on 31 October 1994, looking forward to food and drink and a bed. But they found that, here, transfer to the hotel was tediously slow: there was a thirty-minute bus ride to Tagrin Ferry Point; a two-and-a-half-hour ferry trip to Government Wharf Ferry Point in Freetown; and finally a taxi to the Mammy Yoko Hotel, which they eventually reached at around 2.30am. They were contracted to provide security at the Omai Gold Mine and Golden Star Resources concession at Baomahun. For Fred, the contract was to open one of the most important periods of his life – a period in which he would form a deep friendship with a Sierra Leonean Chief, and one that would see him in combat again.

Soon after their arrival though, Fred had an introduction to the deceptions and graft that were common in everyday life. At the end of their first day, as they were having a meal by the hotel pool, a group of girls appeared and asked if they could join them. The girls said that they were refugees from the war in neighbouring Liberia, that they were all living rough in a tiny room and had to sleep on the floor. Fred and his colleagues felt sorry for their plight and offered them food. However, if they were to allow them to share their rooms, Fred knew that because of colour, his five colleagues would be compromising themselves in the eyes of the white community and the client company, whereas he would not. And so, on the understanding that it would only be for one night, Fred let the girls spend the night in his room; the girls slept on the bed; he on the floor, using his belt order for a pillow.

Next morning he left for work. But when he arrived back at the hotel at 5pm, one of the girls was still in his room. In response to his asking her why she was still there, she said, ‘You promised to pay me $100’. Realization dawned on him; he was being taken for a patsy, and in a flash of anger he said, ‘What $100? I never promised to pay you’. His room was on the third floor and he opened the window and told her that he was going out. And he said, ‘But when I come back, if you’re still here, I’m going to throw you from the window’. He took 10,000 leones (SLL) and put them on the table and said, ‘That is it finished’. Fred learned later that the girls were not Liberians but local girls working a racket with the hotel’s security staff.

That incident seemed to take on new life in expatriate folklore in Freetown, because more than four years later, in January, 1999, a British journalist in the, by then, war-torn capital wrote, under the headline, Street Life: Freetown: Mercenaries, prostitutes and other hotel guests, a sensational, heightened account of it and why it took place, as though it had just recently happened.

Fred, 58, took seven prostitutes up to his room the other night…. the adrenalin of dicing with death seems to make everyone hungry, thirsty and rampant.1

To be sure, the insurgency situation in the country had deteriorated to such an extent by 1999 that the journalist’s use of the word mercenary had resonance then that it would not have had four years earlier. Even so, at the beginning of November 1994, security was a key issue for the mining concerns in Sierra Leone.

The government of the day was a military junta, the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC), headed by Captain Valentine Strasser. From 1991 an insurgency war was being waged in the eastern part of the country, allegedly fomented by a warlord, Charles Ta

ylor, from neighbouring Liberia. His protégé in Sierra Leone was Foday Sankoh, a former Sierra Leonean soldier-turned dissident who learned his tactics at a guerrilla training camp in Libya. Sankoh was attempting to take control of the diamond rich areas of the country. His pillaging was notoriously callous and barbaric: he had a ‘pay yourself ’ policy for his followers of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), encouraging them to kill, loot and rape with impunity.

Alastair Riddell had been contacted by Golden Star Resources who wanted to develop their operations into and across Africa.

I was asked if I would head up a team to develop the exploration site, and I was authorized to hire a small team. Fred was first on my list, for I knew he had just come back from Guyana, as we kept in constant touch. He readily agreed to join me.

We deployed in October 1994, and went to work with gusto, carrying out a recce of the mine, fortunately on the day of a Board meeting, when we were able to report the success by SATCOM from the site. This was a huge step forward, as the country was mired in inefficiency and lack of direction: authority was questionable, and corruption was endemic with all the associated difficulties. We made huge progress, much of it with Fred’s help always covering my back as we went from negotiation to negotiation with government ministers (all about 30 years old), the army and the police.2

As the newcomers in the business, the team that Fred was part of had to establish an office in Freetown and a base in Bo where the concession was located, while, at the same time, trying to ensure that they were not treading on the special preserves of established companies. They took over a large walled compound in Bo and two other properties; they tried to find out the best airfields and the best hospitals for medivac, if they took casualties; they took advice on the routes to take and the routes to avoid; they read up on the regulations that applied to the mining industry in Sierra Leone; and they found out what other companies paid their people.

One particular meeting stands out for Fred. It took place at a rutile mine. The head of security at the mine was a Briton who lived in South Africa,

He gave me the impression that he ‘knew it all’ and ignored me completely, which was very rude I think. Regardless of what he thought of me and my ability, at least he should speak to me instead of ignoring me completely and only speaking to Roger England, our medic, who was ex-Rhodesian Army Medical Corps, whom Alastair recruited because of his medical and African background. The British guy, the head of Security, was saying that if you do the security job properly, you’d have about sixty pairs of eyes to give you the information on what is happening. He said that if anything was happening within a hundred miles around he would know about it from his intelligence.

That boast was soon to be put to the test.

Over the following weeks insurgency activity intensified. Most of Fred’s company returned to the UK for Christmas. Fred stayed behind; his job was to monitor the situation. And it was during this time that he began to get to know Regent Chief Samuel Hinga Norman, a Mende. It was in his chiefdom, in Bo, that the mining concession was sited; and Chief Hinga Norman was liaison officer to the company. Alastair had formed a very favourable impression of him, right from the start.

This was when I met Chief Norman who was my local adviser. He was former British army, and the impression I got was that was indeed a wonderful man, so pro his country that he once said to me, ‘What we need is the British back to sort out this mess.’ Prophetic words indeed in the light of what was to come over the next few years.3

Fred too observed their liaison contact closely: he tended not to wear western dress; he held himself erect; he walked quickly with a walking stick; and his shoes were always highly polished. That intrigued Fred, because from his experience, someone whose shoes were always highly polished was likely to have been an officer. And such was the case with Hinga Norman: he had served in the British army, had trained as an officer at Mons Military College and for a time was stationed in Germany. After Sierra Leone became independent, he served as the first ADC to the commander of its army, Brigadier Lansana. However, it was the character of the man that made an impact on Fred. When you engaged with him, he looked you straight in the eye. And it soon became obvious to Fred that he was not motivated by self-interest – his concerns were the wellbeing of his people.

About this time, the RUF rebels attempted to take over the town of Bo. Armed with AK-47s and RPG-7s, they made a dawn advance towards the headquarters of a local defence militia, the Special Security Division. Now there was also in Bo a detachment of the Sierra Leone army stationed in the west of the town. The rebel incursion, though, was towards the town centre via New London junction. Fred was in Freetown at the time and so the situation was reported to him later. The Sierra Leone army unit made no attempt to leave its barracks, but the people of Bo were not prepared to give up their town to the rebels. There is a large student population in Bo; and Chief Norman, dressed in white, assembled a group of civilians and students. Armed with sticks and clubs or whatever weapons they could get their hands on, and with Chief Norman at the head, they massed and confronted the rebels. This confrontation between a group armed with automatic weapons and rocket propelled grenades and a motley assortment, whose strongest weapon was moral force, had a strange outcome: the rebels backed off and withdrew. The Bo youths then set up checkpoints to control movement into the town. Only at this stage did the army make an appearance, suggesting to the civilians that they should leave the security to ‘the professionals’.

A newspaper’s headline summed up the people’s frustration with the army’s lack of convincing response, ‘Enough Was Enough’. It is true that the Sierra Leonean army was beset with deep-seated problems that only reform and professional training could resolve. Its complement had been enlarged at such a rate that its recruits were inadequately trained. To boost numbers even convicts were allowed to join. Underlying all that, soldiers were paid a pittance and had to forage for themselves as best the could. Against the background of increasing terrorist activity, and the RUF leader encouraging his followers to pay themselves, the allegiance of military personnel could not be relied on. Hence the term sobel was coined: soldier by day, rebel by night.

On Monday 2 January 1995, six days after the rebels’ attempt to take the town, Fred drove back to Bo. He sat in front with his driver. The security company was not authorised to carry weapons – if they had been armed, most likely, they would have been shot at by the Sierra Leonean army. Working in this situation where rebel activity was becoming bolder and incipient anarchy loomed near, Fred carried twenty-one years of SAS experience to guide him. He was prepared to balance risks and act on split second judgement; and in the months ahead, he was going to have to train and motivate men who lacked his zest for action.

He began with his driver. There was the likelihood that as rebel groups moved westwards they would set up Illegal Vehicle Checkpoints (IVCP) in the country areas. Anticipating that, Fred explained to his driver what he wanted him to do.

Slow down, as though we’re going to stop, release your door catch, put the vehicle in second gear and drive as close to them as you possibly can. And when I say ‘GO’ kick the door wide, put your foot on the accelerator and drive like mad. The door will open unexpectedly on the nearest of those manning the IVCP and hit them; and I do the same with my door – I kick it open so that both doors get those manning the IVCP.

That was the hope. And his response to the man’s unspoken scepticism that they could come through alive, ‘Otherwise! It’s better to die trying than to die like a sheep’.

That afternoon, as Fred was been driven back to the mining concession, the rebels attacked and burned the village of Buyama, about 12 miles from Bo. What would be their next move he wondered? He had been booked into the Sir Milton Margai Hotel, and, when he checked in, he made a point of telling them that he would be staying about a week or ten days. When he met some of the mining company’s workers on site he gave them the same story. But he was ranging over o

ther options.

Throughout his time in the SAS, Fred had extensive training in counterterrorism, had fought insurgents in several countries and therefore had insights into how insurgency worked. He assumed that although the rebels had been baulked in their attempt to intimidate the citizens of Bo they would not give up. Foday Sanhok, leader of the RUF, had been trained in Libya; he had probably been briefed on Mao Tse-Tung’s dictum that ‘the guerrilla must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea.’ Some of Foday Sankoh’s RUF would be mingling among the local people, probing for vulnerable spots and easy targets. Until they made their move, though, it was not possible to determine friend from foe. However, there was one likely target – Chief Hinga Norman. Hinga Norman had motivated and led the town’s resistance to the rebel incursion the previous week; he was also the mining company’s liaison officer, and he lived in a house in the city. With these thoughts in his mind, Fred went about his business for the remainder of Monday and again on Tuesday, paying close attention to what was happening around about; but on Tuesday he invited Chief Norman to his hotel for dinner that evening.

They had a convivial meal and Fred voiced no concerns about Hinga Norman’s safety. However, he had observed him closely over the few weeks they had been together and he made some shrewd deductions: Hinga Norman’s insistence on appearing in public wearing highly polished shoes was a carry-over from his officer training in the British army; he was likely to be just as fastidious about punctuality. And so after they finished their meal, Fred invited him to join him for tapas at the hotel the following morning at 10am sharp.

Next morning Fred left the hotel with his driver after 9am; however, he returned to it just before 10am. Next, he told the driver to wait in the car, and he went into the hotel, with his radio handset to his ear. As he was walking across the foyer to Reception, he put the phone away, went up to the desk and said, ‘I’ve just had a call, and I’ll have to go back to Freetown. Could you give me my bill please?’ As he was paying the bill, the hands of the clock on the wall in Reception were pointing at 10 o’clock; Chief Norman arrived and Fred took him by the arm and led him straight to his waiting vehicle. No observer watching Hinga Norman’s movements could have had an inkling that he was about to be moved out of Bo.

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars