- Home

- Ross, Hamish

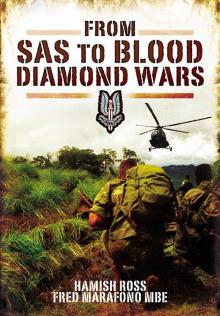

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars Page 6

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars Read online

Page 6

Hinga Norman asked me how we could use the Kamajors, how we could utilize them. Which I did, and I went into the Kono district and I met a guy by the name of Randolph Fillie-Faboe; he later became a Minister in the SLPP [Sierra Leone People’s Party]. And we used the Kamajors to a very great extent, and very, very positively. And we had very good results with the Kamajors in working with them, supporting them on their level; and they were giving me vital information. And a number of my operations, with specific reference to the Gandorhun area, came from the Kamajors. They brought me information on a daily basis; and Fred and I were always co-ordinating on this; and he always said to me that we should use the Kamajors more and more, to make them figure prominently as a local militia as they had support from the local people and so on.9

At the same time, as commander in an area, ‘Roelf worked hard to build trust with the local population.’10 He ordered the removal of anti-personnel mines that the Sierra Leone army had planted; he established a clinic and combined local administration council.

Executive Outcomes had also the task of supporting and training the Sierra Leone army. As a result Fred’s role broadened: he was asked to show army personnel how to organize and take a food and fuel convoy which would travel from Masiaka up country to Bo, Kenema and Daru. Dealing with convoy ambush had been part of the jungle warfare course he had been responsible for in his past life, so he was the ideal man to instruct the Sierra Leone army.

By this time, Simon Mann, who put Fred up for Executive Outcomes, was receiving a lot of feed-back on his performance, and wrote to him on Tuesday 11 July 95.

Dear Fred

I am very sorry to have been unable to see you since you started – I have been 100% entangled first in Luanda and now London. All reports are that you have done a great job, as I knew you would, and are the man for that job.

The bearer of this letter is an old hand in this game, and he can explain to you. We are all working hard to think thru the SL situation. To this end can you please trust R —— [the bearer of the letter] entirely and allow him to debrief you fully on all aspects of the operation.

R —— has a non-disclosure strategic brief from Tony and myself, and, in the course of talking to him, it is likely that changes and developments to your role, should you be interested, will raise their head. Please accept this letter as a note from me that you can develop this line of approach should you wish: Tak sends his best:

All the best from me and many thanks again

Yours Aye

Simon Mann.11

Although the major threat to Freetown had been lifted, the nature of the guerrilla war meant that there were rebel units scattered around the country, in touch with their headquarters by radio. And so frequent were the attacks on convoys between Masiaka and Mile 91that it became called ‘Ambush Alley’. Fred was tasked to organize the convoy and take it along ‘Ambush Alley’ to Mile 91. At Daru, the ultimate destination of the convoy, there were stationed some units of the Guinean army, whose government had sent them as a token force to show solidarity against the RUF.

Systematically Fred set about the assignment. He wanted backing from the top and so he met Tom Nyuma, Deputy Defence Minister in the military government. Civilians would drive the convoy vehicles, and Tom Nyuma arranged for Fred to meet the chairman and the committee of the drivers’ union. Fred outlined his requirements: the committee should select the drivers who were to take part in the convoy; the number of vehicles should be not more than fifty – which meant it was a large convoy -; all the vehicles were to be road-worthy; they should have a minimum of six good tyres; they must not be overloaded; and Fred made plain that he would inspect each vehicle. When he later met the drivers who were allocated to the convoy, he briefed them that if there was a breakdown, everybody would stop – no vehicle was to be left.

And I told them that if we should come across an ambush what I wanted them to do. ‘First of all, switch the engine off, and leave the vehicle keys in the ignition. If the ambush is from the right, de-bus from the left and move away from the vehicle, get down.’ We would sort the ambush out and then when we finished we would organize and move on again. The reason why I didn’t want them to take the vehicles’ keys – and I was proved right – was that if they came to start the vehicles and there were no keys, they would run.

In addition to the fuel and food trucks there were three four-ton trucks with soldiers, two Land Rovers, two vehicles with 12.7 anti-aircraft guns and recovery vehicles. There was also an Executive Outcomes helicopter, an Mi-17, not a gunship, to fly top-cover.

Finally, the day came for the convoy to line up. From past experience Fred anticipated that sod’s law would kick in when the convoy assembled. He was not wrong: they were late in getting off, and at the last minute the Guinean army contingent turned up with their trucks full of supplies for their own troops.

What I didn’t know at the time: they were doing business – all these trucks were loaded with goods – they were doing business up country. But worst of all, before we set off, these people were drunk. They were all big talk; they wanted to be in the lead.

The low opinion that Fred formed of Guinean officials when he was involved in the release of the hostages a few months earlier was now transferred to the military of that country. However, he had to step lightly too: the Guineans were overall under the control of the Sierra Leone army but their men took their orders from their own officers; and there was the lingua franca problem – Guinea is a francophone country, and French was the second medium for communication. Over and above that, there was a heavy hierarchy of Sierra Leone officers to relate to: the army sent one colonel, three majors and six captains. It was not a case of Fred being outranked, he had no rank; but he was the professional leader of the convoy and the over-representation of officers was so that they could learn the principles involved.

The convoy lined up with the Guinean contingent further back, and Fred gave the signal to start up the vehicles. The helicopter was in the air, and the convoy moved off. It was not all that long before they drove past the site of an earlier ambush: the roadside was littered with burnt out trucks, bloated bodies and partial skeletons of victims. When the front of the convoy reached the top of Magbosi hill, Fred received information that one of the rear vehicles had a puncture. He ordered the rest of the convoy to the top of the hill; they de-bussed and the protection team formed an all-round defence; and they waited while a wheel was changed and the rear group caught up. Then the convoy moved off again.

Further along the route, gunshots suddenly rang out from among the vehicles. Fred stopped the convoy and asked who was firing. He was told it was the Guineans. He ran to their position, demanding to know who they were firing at. One of them said, ‘The rebels.’ Fred was on the point of losing his cool. Angrily he faced them, ‘If there were rebels, I would be the first to fire.’ The effects of drink were still apparent on the Guineans; it could have turned nasty at this point, but suddenly Fred’s radio crackled into life; it was the voice of the EO helicopter pilot, Chris Louw, asking about the shooting.

I told him it was the stupid Guineans. The cloud base was getting low and I also thanked Chris Louw and told him to go back to base. He was reluctant, but the cloud base was getting lower and to fly the helicopter at low speed would be risking both the helicopter and lives of the crew. As I was speaking to Chris, one of the Guinean officers signalled to me that everything was OK.

So tension relaxed, and they carried on without top-cover or further incident until they reached Mile 91 around 7pm. There the convoy passed to the control of Colonel Carew of the Sierra Leone army. Their task completed, and fortified with a cool soft drink, Fred said that they would set out on the return journey. The Guineans were surprised at this decision; they thought they were to stay overnight at Mile 91. That denied to them, they wanted their vehicles to be in the centre of the small returning military convoy. Fred refused that request, telling them that with their two armoured vehicles their place was

at the rear.

The return was uneventful until they were not far from Masiaka where they came upon one of their convoy’s food vehicles broken down, the greatly relieved driver sitting alone in the dark. His truck had broken down soon after the convoy started and it seemed that no one wanted to tell Fred and delay the convoy. The recovery vehicle was hitched up and the truck was taken to Masiaka and turned over to the local army unit and the police.

Inducted into the management of convoy movement, the Sierra Leone army officers who had accompanied Fred were supposed to be ready to take the next one on their own. Fred’s job for this convoy was to organize it up to the point of departure. He followed the same procedure with the drivers’ union. All the officers had been with Fred on the first convoy; the colonel was in charge, and one of the majors was deployed at the front, one at the back and then there were the captains.

When I set them off, I realized that at the front they were driving like mad, but I was only with my driver, nobody else at that time. So what I did was after the last vehicle set off – I couldn’t leave them like that – I had to chase the convoy. My driver and I, we drove like fury and caught up with the convoy quite a way on when they stopped at this village. So I reassembled all the vehicles and I said, ‘No, you cannot do that; who is going to protect the rear? You’ve got to go as a group and fight as a group.’ I nearly went on that convoy. I nearly joined the convoy but my driver would have to drive back on that road by himself. I looked at him and he wasn’t very happy. I said, ‘Don’t worry I’ll come back with you.’

On the way back to Freetown, they passed through Masiaka and got as far as Waterloo when Fred received word that the convoy had been ambushed. He turned and headed for Masiaka, intent on mustering reinforcements from the local military unit and carrying on to relieve the convoy. He knew that this time the Executive Outcomes’ helicopter could not be spared: it was in service, ferrying food and supplies from the transport plane that flew in from South Africa once or twice a month and kept EO self-sufficient. So they could only relieve the convoy by road.

He reported to the local Maskiaka military commander, a major, who agreed to provide some men. Exasperated by the sight before him, Fred silently contrasted the professionalism, dedication and discipline that went into convoy-ambush exercises at the jungle warfare training centre in Brunai with what he was presented with.

The major was in flip-flops, a pick-up truck of ten to twelve men, some with only one magazine for their weapon. I said, ‘How are you going to fight a war?’ And an old colonel, a nice old boy, stepped forward and said that he would come with me.

So this motley assortment, more like Fred Karno’s army than a group of professionals, set out in the pick-up truck. They drove only about six or seven miles when they had a puncture. There was no spare wheel. Fred had every right to despair, ‘It was a right Mickey Mouse convoy relief.’

But they went back to Masiaka where Fred phoned Tom Nyuma and pleaded with him – could he not send a helicopter. Tom Nyuma responded on the instant that he would come by road with reinforcements. He did not take long and arrived with four Land Rovers loaded with soldiers; and they drove to the scene of the ambush at Magbosi.

When we arrived it was getting dark. The rebels were still there looting: they took two of the tankers and started to siphon the fuel. So we got out and walked down and cleared the ambush area and stayed there. And what we did, we set up a group at the front and a group at the back and then we held the ground there. And what was incredible, as we were clearing the area, we saw the body of this old lady the rebels had killed; and you know it was horrible, with this big stick stuck in her. So we covered her up and when the operation was finished we buried her with dignity. That was the rebels!

The following day, they held the ground and cleared the area. And from what they discovered it was obvious that local people had been in cahoots with the rebels. The locals benefited from ambushes. Fred and the soldiers found a warehouse where the loot was stored. That indicated the likelihood of a rebel base quite near, so Executive Outcomes mounted an operation, located the camp, and cleared it.

In this way the war continued to be fought, with Executive Outcomes seeking out rebel camps in the bush and taking the fight to them, not allowing the RUF to determine where encounters would take place. On many operations, EO were aided by information from groups like the Kamajors; sometimes the Kamajors took action themselves against the rebels.

As the year came to a close, talk of elections for a restored democracy was in the air. The military government, though, started dragging its heels; there was internal dissention, and in February 1996, Strasser was ousted as head of the ruling elite by his deputy, Brigadier Julius Maada Bio. However, there was overwhelming support from the people for the restoration of democracy. That elections in Sierra Leone were being planned only months after the capital city was on the point of being taken by the RUF was possible only as a result of the operations of Executive Outcomes. As the first President of the restored democracy would later put it,

Executive Outcomes was the only credible and dependable military outfit opposing the rebels.12

But what would happen in the future when the company’s contract came to an end? The RUF was still a force to be reckoned with; there had been no miraculous transformation of the Sierra Leone army; and the Kamajors were in reality a militia. There was still a case for training and arming them.

Fred had been thinking about the problem for some time, and he came up with a clever, self-funded scheme to raise money to train, equip and arm a force of Kamajors under the leadership of Chief Hinga Norman, by setting up a company to trade in diamonds and sell them abroad. He discussed it with Chief Norman, who liked the idea but cautioned first of all, that neither he nor Fred knew anything about diamonds – although he knew people who did; and second that he did not want to be closely involved, because diamonds tended to destroy friendship – and he would rather have friendship – , but he would help a company that Fred was part of.

Next Fred contacted his old friend from KAS days, Pete Flynn, and invited him to Sierra Leone. Pete, it will be recalled, was not only ex-SAS, he was a pilot; and he, in turn, got in touch with Simon Mann, who was working with a security company called Ibis. The company did not have a presence in Sierra Leone, but Simon Mann thought it would be useful if Pete went there as a foot on the ground to assess the possibilities for security work with a flying capability. And on that basis, Pete Flynn joined Fred. After assessing the situation, though, Pete felt that there was no useful role for airmanship, but recommended to Simon Mann that a better use of his time would be to help establish a scaled-down version of the model for the training of a local force that could stand up to and defeat the RUF.

The diamond fields of Sierra Leone were one of the country’s main resources. Its industry appeared to be regulated but in reality there was wide-spread corruption and exploitation: an illicit market operated with people stealing them from a mine and secreting them, or finding them by searching in a river bed. But at this point the thief, or the finder, had a problem, which Pete outlines.

Then they used to try and sell the diamonds; and the only way they could sell the diamonds was to the local dealer – they were Lebanese mainly, quite a cross-section, Dutch even. But they used to rip them off: you’d get a $25,000 diamond and they would give them maybe $50 or $100 for it. So we said if we could get in with those people down near Kenema, we could buy the diamonds at a fair price and take them over to Antwerp, sell them, get the money and bring the money back and give the money (not all the money) to the Chief – because we needed working capital. The basic principle was to give them a certain amount and then they could buy weapons to set up what Fred was setting up and also buy rice and tools and all the rest of it. So basically they’d be able to fund the setting up of that. Which was right. 13

They cleared the idea with Simon Mann and his partner Tony Buckingham. Then Fred and Pete set up a company, Inter-Afrique, whos

e business was mining and general trade; they registered it in Freetown, under the Business Registration Act, on 5 March 199614; and they took on two local partners: George Jambawai and Humphrey Swaray, who was the manager of the international airport at Lungi. Pete put up $25,000 as working capital and Simon Mann put in a similar amount. There were five shareholders: the four partners and Chief Sam Hinga Norman, each holding 15% share in the capital of the company, with 25% assigned to the company. The Commissioner of Income Tax assessed the company’s tax liability for the tax year at SLL 960, 000, and Fred paid over a cheque for SLL 251, 475 in payment for 1995/96.

However, on the political front momentum was gathering for the forthcoming elections, and on 22 March, Chief Norman wrote to the company secretary:

Due to my possible involvement with the elected government of Sierra Leone, I hereby relinquish any rights or benefits offered by the company, Inter-Afrique (SL) Ltd, and authorize you to transfer my shareholding back to the company free of charge.

Signed this 22nd day of March 1996.15

Operational responsibilities in the company were allocated along the lines that Fred would obtain a dealer’s licence, and Pete was to become familiar with appraising uncut diamonds.

So they sent me off to Antwerp to do a familiarization course to get familiar with appraising rough, uncut diamonds so that I could assess them. So I had to learn as much as I could about diamonds. Then I could assess, pretty well, uncut diamonds – not cut ones, I wasn’t interested in that – look at the size, the colour, the clarity and all that.16

Fred, meantime, had to go to the UK but before he left, however, he completed and signed the requisite documentation, along with a photograph, applying for a diamond dealer’s licence and left it with their partner, George Jambawai, to register.

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars