- Home

- Ross, Hamish

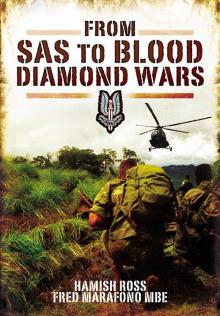

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars Page 10

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars Read online

Page 10

I got to Conakry a couple of days later, and Sam came and saw me at my hotel, the Camayenne, I said, ‘Have you seen Kabbah yet?’ and he said no. Then I saw Kabbah and I said, ‘Have you seen Sam Norman?’ I said, ‘You know he’s here in Conakry.’ Kabbah said no. And I thought this is funny, I mean these are the two key people and they’re not even talking to one another. And I’m still learning, feeling my way about those relationships; it would be years later I realized the people who were anti-Sam and dripping it into Kabbah. But I said to both of them, ‘Look, whatever your personal differences are you two have got to be talking.’ I said, ‘These are crucial times,you must talk to one another.’

And Sam made the first move and went and saw Kabbah. It was one of those things he always said to me in later years, he said, ‘That was one of the best pieces of advice you ever gave me. You were right. I shouldn’t have carried on like that,’ vis-à-vis, you know what Kabbah’s like and so on. I had a hand in pushing them together; and I would keep in touch with was going on. He would send one or two of his people to keep me informed about what was going on in Liberia. But there was not a lot of contact, but in our one-to-one discussions, I think we established a relationship. I think we trusted one another; we had an admiration for one another, for what we were both doing.9

In contrast to Freetown, Kono remained calm, thanks to Lifeguard and the SSD. But for how long? Unexpectedly, Fred was hit by a mild bout of malaria. The security company needed to be resupplied, and this could only be done by air. A resupply helicopter flight was due on the afternoon of the 14 June, and Jan told him he should accept being invalided out on it, along with some of the foreign nationals; otherwise, he would have to be evacuated to Guinea by road, and the roads could be closed. The rest of Lifeguard, however, would remain in Sierra Leone for the time being. So on 14 June, Fred and eight others, including Russians and Sierra Leoneans, were air-lifted from Kono to Guinea.

They landed at Conakry around 7pm, disembarked and went to arrivals. And that was as far as they got. Out of the blue, Guinean Immigration decided that they had no permission to enter the country, and informed them they had to return to the helicopter that brought them. There was no alternative but to comply. They were sitting in the helicopter, discussing possible options, when one of the Russians asked if anyone had a contact number for their country’s consul in Guinea. By a stroke of luck Fred had kept the Honorary British Consul to Guinea’s business card − her daughter had given it to him two years earlier when her mother was out of the country and Fred required assistance to receive hostages at the country’s border −, and he now fished it out from the back of his ID card folder.

The pilot called up the airport’s control tower and asked for a landline connection to the helicopter. A call was put through to Honorary Consul, Val Treitlein, who not only responded but came to the airport. She asked Fred if the nine were all British, and he said they were. The Consul then informed the Guinean Immigration officials that these people had the right of access to the country; and the officials did not contest it. Fred warmly thanked Val Treitlein, and then took a taxi to a hotel, because as far as he was concerned, he would not be presenting himself at a hospital for treatment: he would use self-medication.

When Sam Hinga Norman was evacuated by helicopter to the USS Kearsarge on 30 May, he knew very clearly what had to be done to bring about the restoration of the democratic government of President Kabbah: it had to be achieved through armed conflict, led by, or reinforced with, militias such as the Kamajors. It was the same idea that he and Fred had endeavoured to introduce to fight the RUF, using two different models in both 1995 and 1996. Each time, the problem that defeated them was the project’s funding. Now, on 30 May 1997, on board the Kearsarge, Hinga Norman approached another evacuee, an Israeli businessman, Yair Galklein, who was involved in the diamond trade, and told him that he was seeking assistance from companies in the diamond industry to bring about the restoration of the government of Tejan Kabbah.10 To that end, funding was needed to train, arm, feed and provide crucial logistical support for Sierra Leonean militias. In subsequent discussions on board ship, Yair Galklein and some of his associates in the industry told Hinga Norman that they would be staying in Guinea at the Mamado Hotel.

The USS Kearsarge weighed anchor and sailed north, and its passengers were air-lifted to Conakry. Already in the country’s capital was President Kabbah, who had been accommodated in the government Guest House by the Guinean President Lansana Conté. Although Peter Penfold had encouraged both of them to get together, fundamental differences surfaced right away between Deputy Minister of Defence, Hinga Norman, and President Kabbah on the strategy for restoring democracy to their country. The President put his faith in diplomacy; Hinga Norman argued for armed intervention,

driven by a Sierra Leonean fighting force. The Kamajor militia of the Southern and South Eastern Districts would form the bulk of the force, under his direction and command. Hinga Norman invited great risks to his life and his credibility to put his vision into practice.11

As far as Hinga Norman was concerned, sitting in Conakry was the equivalent of Nero fiddling while Rome burned. He had to move to Liberia, where ECOMOG troops were based, infiltrate into Sierra Leone, and organize the Kamajors into a fighting force. First there was business to attend to in Conakry. He went to the Mamado Hotel and met Yair Galklein and some of his business colleagues. Their response to his request for their help in restoring democracy was the promise of the supply of food to him in Liberia to feed the Kamajors.12 Then there was a need to find professional trainers to train a fighting force. So, for a short time, Hinga Norman moved back and forth between Liberia and Guinea, building a support network.

It seemed as though an alternating current flowed through Fred’s experiences in Guinea: negative to positive at the airport; and that oscillation continued throughout his stay there. Among those who had arrived in Conakry was Fred’s business partner, at Cape International, Murdo Macleod, who had flown there directly from the UK. The two partners were no longer in a strong position: funds had all but dried up in the company’s account since the mining operations at Yara were suspended. Fred, in the interim, had been employed by Lifeguard, and on the payroll of Branch Energy, but in reality had not yet received any money. In Guinea, he was accommodated in a hotel on a room-only basis, and he had to eat at a food stall in the street. All the while, feeling rough and weakened, he was recovering from malaria. It was a low period for him. And this was how he was when Sam Hinga Norman was told Fred was in Conakry.

Hinga Norman was on one of the fleeting visits he made to Guinea at this time; he came to the hotel to meet Fred, and told him what he was trying to achieve, from a base in Liberia. Fred asked if he could be part of it. Hinga Norman’s response was positive: ‘Fred, you do not have to ask me. I would be delighted to have you with us.’ But when Fred revealed that he could not even pay his fare to Liberia, Hinga Norman told him that life was very basic for him and his followers, and there was no excess of funds, and he suggested that Fred should phone Tim Spicer in London. Tim Spicer was Director of the private military company, Sandline International, which itself was part of the group of companies associated with Branch Energy. Hinga Norma had already been in touch with Tim and made soundings for external support, probably in the form of weapons, but also likely in the form of personnel. After this brief meeting, they parted, and that was the last Fred saw of him until they were to meet up in Liberia.

Fred’s bout of malaria went through its stages, aided by the oral medication he was taking. When he felt he had recovered, he contacted Tim Spicer, who seemed to already know about Hinga Norman’s overall strategy. Tim Spicer’s response to Fred was immediate and precise. He agreed to employ him, but he was to work with Hinga Norman, but not for him: he was to work for Tim Spicer, and report to him what Hinga Norman planned to do before he did it, for Tim did not want surprises. Fred accepted the terms as Tim laid them out. His next step was to meet with a represen

tative of Branch Energy in Guinea (Brig Sachse, formerly of EO)draw an advance and get himself to Liberia. However, the handwritten note he received authorized him to draw only $700 as an advance on his salary. He argued that it was not enough: he had no network of contacts in Liberia. The advance was increased to $1,700; Fred organized himself a visa for Liberia, and bought his air ticket.

In Liberia, as early as 18 June, Hinga Norman had given a signal to his countrymen, broadcasting from a clandestine radio, urging armed resistance to oust the AFRC, arguing that negotiations with the coup leaders had proven futile.13 The junta had swung from one policy of proclaiming it would disband the Kamajors to the other extreme of inviting them into the government. A Kamajor spokesman rejected this idea, and shortly afterwards, from a base in Kenema, another spokesman claimed that the Kamajors would march on Bo. Skirmishes took place in early July, and it was reported that Hinga Norman was seen on Sierra Leonean soil in the area of the Mano river bridge which was being fought over by Kamajors and AFRC. This brought the response from the AFRC that President Kabbah, with the assistance of the Nigerian Foreign Minister, was arming the Kamajors to wage war against them.

Hinga Norman was clearly emerging as the prime mover in resisting the coup: he raised funding; he formed some structure for the Sierra Leonean militias; and he infiltrated into Sierra Leone to establish advance bases for military strikes. At an international level he formed influential partnerships. He was friendly with a Sierra Leone clergyman, the Reverend Alfred SamForay, who, though based in the USA, had a wide range of international contacts. The result was that the Rev SamForay became Secretary-General of a group known as the Sierra Leone Action Movement for the Civil Defence Force (SLAM-CDF). SamForay also linked with President Kabbah in Guinea, and confirmed later that Kabbah, ‘greatly welcomed any assistance we would give to Chief Norman and the CDF.’14

Fred’s destination when he arrived in Monrovia, capital of Liberia, was the Sierra Leone embassy. A surly uniformed officer told him that former Deputy Defence Minister, Sam Norman was staying at a house belonging to the Nigerian Ambassador. Driving through the streets of Monrovia during the final days before the country’s presidential election, Fred came across the most bizarre partisan electioneering he had ever seen. Charles Taylor, the revolutionary leader who had waged the civil war which brought about the intervention of the ECOMOG force, and who allegedly sponsored and bankrolled the RUF in Sierra Leone, was a candidate for the presidency, and groups of his supporters were moving through the streets wearing white T-shirts emblazoned with the slogan, ‘You killed my mother, and you killed my father, but I’ll vote for you’. That really got to Fred; he thought it was a perversion of a basic sense of justice: ‘If you killed my mother and you killed my father, I’ll kill you.’

When Fred found Hinga Norman, he was in the process of moving out of the ambassador’s house, because he had to be where his people had access to him. He moved into a small house in the campus of the Ricks Institute, a distinguished college about 16 miles out of Monrovia that had been badly damaged and plundered during the country’s civil war. The Institute was taken over by Nigerian troops of ECOMOG who were stationed in Liberia. Hinga Norman’s base was modest by any standard: a two-bedroom house; he and his wife and daughter had one room with mattresses on the floor; four women shared the other room, some men slept in an outer building.

At their first meeting together, Fred told Hinga Norman about his briefing from Tim Spicer: he was to work with the Chief, but for Sandline, and he was to advise Tim of Chief Norman’s major plans in advance. The Chief was perfectly equable with that, and said that Tim Spicer had been of great service to his cause. Indeed, in the course of time, Sandline gave the Chief $25,000, of which $20,000 was spent on communications, and $5,000 on medicine and food.

The road ahead, however, for Hinga Norman was far from smooth. A new factor emerged which made life dangerous for him in Liberia: on 19 July Charles Taylor was elected the country’s president. And true to his trade, it did not take him long to put out an assassination order on Hinga Norman.15 However, so long as Hinga Norman was escorted by ECOMOG soldiers, he was safe. Working more openly, at head of state level, Charles Taylor also wrote to President Kabbah, objecting to the active presence of the former Deputy Minister of Defence of Sierra Leone in his country.

President Kabbah, still based in the government Guest House in Guinea, along with several of his ministers, formed a War Council in Exile. Its status was advisory, and its remit was to discuss ways and means of ending the war through dialogue with the AFRC . The British High Commissioner to Sierra Leone, Peter Penfold, was also now based there, demonstrating Britain’s support for Kabbah. In addition, Britain provided funding of £150,000 to acquire and maintain an office in Conakry for the Sierra Leone government, and Peter Penfold arranged for equipment to be bought so that a radio station could operate for the government in exile.

Dr Julius Spencer, a Sierra Leonean academic, flew from the States and he and two others set up this radio station in a tent at Lungi airport which we called Radio Democracy 98.1, and through that radio station broadcast to the people of Freetown, just to keep democracy alive.16

High Commissioner Penfold and others broadcast on that wave length, encouraging people to anticipate the return of democracy to their country. The international community had refused to recognize the AFRC junta; Kabbah was therefore still accorded some of the symbols associated with his status as a head of state.

What Kabbah was not, however, was a charismatic leader, who showed by actions and words that he was determined to remove the AFRC junta. He put his emphasis on negotiation with the AFRC/RUF junta, even although his earlier dialogue with the RUF at Abidjan turned out to be appeasement that produced disastrous results. Nor was Kabbah a leader who gave the impression of being in touch with his countrymen and women’s plight: thousands of Sierra Leoneans had fled to Guinea; they gathered and queued for help outside their country’s embassy in Conakry, which was just across the way from the government Guest House where Kabbah was staying; not once in the ten months the junta were in power did Kabbah walk across the way to greet them or identify with them.17

In such a situation, where the Deputy Minister of Defence clearly demonstrated qualities that Kabbah lacked, power politics inevitably came into play among members and officials of the Sierra Leone government in exile. President Kabbah’s advisers were concerned that the power base for dislodging the AFRC lay with his Deputy Minister of Defence and not with the President. Hinga Norman had quickly emerged as the man of action, the leader defending the restoration of democracy in his country through military action. And he had a lot of support. The Nigerian Chief of Staff of the ECOMOG forces in Liberia agreed with Hinga Norma: a united front of Nigerian ECOMOG troops plus the stiffening of Kamajors could defeat the AFRC/RUF.18 But in a real sense, Kabbah’s advisers’ concerns were groundless, because Hinga Norman’s aims were to reinstate President Kabbah; he was not positioning stepping stones towards that post for himself.

Nonetheless, Kabbah wanted to replace Norman as the head of the CDF, or at least limit his power by bringing in another co-ordinator for the CDF in the north of the country. So on 17 August, Kabbah summoned Chief Norman to Conakry. Kabbah gave his Deputy Minister of Defence an ultimatum, either to stay in Guinea and contribute to the War Council in Exile, or return to Sierra Leone, basing himself at ECOMOG-held Lungi airport along with Vice President Joe Demby. To Hinga Norman such a choice was unrealistic as a means of helping achieve the restoration of Kabbah’s government: staying in Conakry as part of the War Council in Exile was futile – it was an advisory body that met to discuss ways of ending the war through dialogue with the AFRC, and he looked on it as a talking shop;19 whereas moving into the Nigerian enclave at Lungi would simply mean an impotent presence on Sierra Leonean soil, unable to move out into the heartlands of the militias.

Hinga Norman, however, had to be seen to comply with his President’s wishes, and after mulli

ng it over he made a quick decision. Ever since he had established himself in Liberia, his trips to Conakry were infrequent and of short duration, and he rarely stayed in the same location more than once. He told Fred that it was rumored there were influential individuals in Guinea supportive in principle of the AFRC; he might find an unexpected problem at a road block, for example. So he varied where he stayed on these visits; on this occasion, he was hosted by Murdo Macleod, Fred’s business partner. They discussed a way round the problem, and hatched a plan, which Hinga Norman later recounted to Fred.

Although there was a shortage of funds in Cape International’s account, the ploy that Murdo came up with required some cash. Hinga Norman would agree to go Sierra Leone, and fly to Lungi on an ECOMOG flight; Murdo, a former RAF fighter pilot, would accompany him on the trip, chat to the pilot before they took off, establishing their shared professionalism; and then, after take off, when the pilot was setting his course for Lungi, Murdo would go up to the cockpit and bribe him to divert to Monrovia in Liberia. And for the bribe, he had a limit of $5,000. Everything worked as anticipated, but Murdo was shrewd enough not to lead with the figure of $5,000: he offered $3,000, and this was sufficient to satisfy the pilot. He diverted to Monrovia and they landed at Spriggs airfield. Chief Norman was back on Liberian soil, ready to carry on preparations for removing the AFRC in the only way that he thought would bring results.

He made several incursions with trusted followers across the border into Sierra Leone to meet militia representatives. He got the agreement of the heads of hunter groups to fight back to restore democracy and re-establish Kabbah in power. He set up an intelligence network, recruited men, established bases and set out recce patrols to various areas that were selected as the first targets, moving westwards from the Liberian border. Then there came a point when the hunter groups like the Kamajors could be brought together at an eastern base. On that occasion, Hinga Norman took Fred with him on a cross-border mission to a pre-arranged meeting.

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars

From SAS to Blood Diamond Wars